Introduction

South Korea's healthcare system is in crisis. A massive strike by doctors has paralyzed hospitals nationwide in response to the government's plan to increase medical school admissions. This conflict has raged for months and reached a critical point.

The government wants to add 2,000 medical students per year-a 50% increase from current levels. President Yoon Suk Yeol's administration announced this plan in February 2024, arguing Korea needs more doctors in rural areas and essential specialties.

The medical community fiercely opposes the plan. The strike started with medical students and residents but now includes professors and private practitioners. As of August 1, 2024, only 9.3% of medical residents were working across 211 training hospitals.

This post goes beyond the surface dispute between government and doctors. I'll examine the deep structural problems in Korea's healthcare system-a system sustained by doctors' sacrifices and price controls that would make North Korea blush.

What is happening with the healthcare system in Korea?

The dispute centers on the government's proposal to increase medical school admissions by 2,000 students annually-a 60% jump from the current 3,058. President Yoon Suk Yeol's administration announced this in February 2024, claiming Korea desperately needs more doctors in rural areas and essential specialties.

The medical community revolted. What began as a walkout by medical students and residents has grown into one of South Korea's largest medical strikes ever, now including professors and private practitioners.

The strike's impact is devastating. As of August 1, 2024, only 981 of 10,506 medical residents (9.3%) were working across 211 training hospitals. While only 51 residents officially resigned (0.49%), many more simply stopped showing up without formally quitting (source).

The government has responded with threats. They've forbidden hospitals from accepting resignations and threatened legal action against strikers. Officials claim doctors are abandoning their duty and endangering patients' lives.

What exactly is the legislation?

The legislation mandates all Korean medical schools to increase admissions by 2,000 students total-jumping from 3,058 to over 5,000 new medical students annually.

Key timeline:

February 6, 2024 Minister of Health and Welfare Cho Kyoo-hong announced the decision to increase medical school admissions by 2,000. February 22, 2024 The Ministry of Education sent out a demand survey to each medical school regarding the allocation of increased admissions. This was a follow-up to the first survey in October 2023, where medical schools initially requested 2,151-2,847 additional spots but then reversed to 350 in January 2024. March 4, 2024 Despite the atmosphere of collective action, universities actually increased their demand to 3,401 in the second survey. March 20, 2024 Prime Minister Han Duck-soo and Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Education Lee Ju-ho announced the results of the medical school admission increase allocation.

The government claims this will fix doctor shortages in rural areas and essential specialties.

Arguments in favor of the legislation

Supporters point to several problems they believe justify the increase:

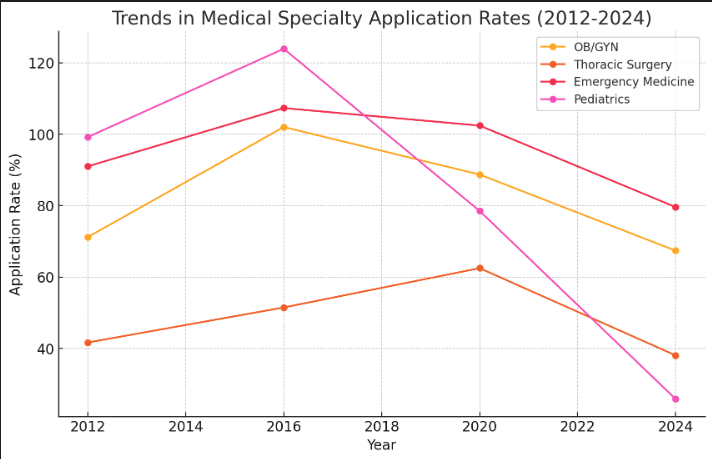

1. Shortage of doctors in vital specialties

Doctors avoid certain essential specialties:

- Emergency Medicine

- Obstetrics and Gynecology (especially for delivering babies)

- General Surgery

- Thoracic Surgery

- Pediatrics (especially emergency pediatrics)

These specialties are essential but unpopular due to poor work-life balance, legal risks, and low pay.

[1] 송수연. (2020, December 5). 갈수록 심해지는 전공의 지원 양극화…"환경 변화 반영". 청년의사 [2] 성서호. (2023, December 7). 내년 소청과 전공의 205명 뽑는데 53명만 손들어…지원율 꼴찌. 연합뉴스. [3] 이창진. (2012, November 29). 인턴들, 복지부 뒤통수…정원 감축후 양극화 심화. 메디칼타임즈.

In 2022 alone, 9,414 patients had to be transferred between hospitals because the first emergency room lacked the right specialists (source). The assumption is that these transfers cause preventable deaths, proving Korea's healthcare quality is poor. I'll debunk this later.

2. Rural doctor shortage

Physician density varies dramatically by region. Korea averages 2.3 doctors per 1,000 people (versus OECD's 3.4). Seoul has 3.1 per 1,000, while rural North Gyeongsang has only 1.4 (source).

3. Aging population

The government's core argument for increasing medical school admissions is based on the aging population. The elderly population (65 and over) is expected to surge from 9.94 million in 2023 to 15.21 million by 2035. As a result, it's predicted that by 2035, inpatient days of hospital stay will increase by 45% and outpatient by 13%. Calculated based on health insurance medical expenses, the demand for doctors quadruples from age 65. Considering this, there's no choice but to significantly increase medical school admissions. https://www.mk.co.kr/news/editorial/10974827

4. Comparatively low doctor-to-population ratio

Other developed countries have greatly increased their medical school admissions for the same reason. Germany, France, and the UK have 4.5, 3.4, and 3.2 doctors per 1,000 people respectively, far more than Korea (2.6). Despite this, Germany plans to increase its medical school admissions from 10,000 to 15,000. France increased its admissions from 3,850 in 2000 to 10,000 in 2020, and the UK increased from 5,700 in 2000 to 9,500 in 2023. Moreover, in France and Germany, even though they are increasing medical school admissions, top talents are choosing engineering over medical schools, which is beneficial for national development. Korea's plan to increase by 2,000 is actually modest compared to these advanced countries. https://www.mk.co.kr/news/editorial/10974827

5. Short consultation times

Korean primary care doctors spend just 4.2 minutes per patient (source)-far below the US (22 minutes) and Japan (10 minutes) (source).

6. High physician income

According to the OECD Health Statistics 2023, salaried Korean physicians earned an average annual income of $192,749 (about 255 million won) based on the PPP exchange rate in 2020, the highest among 28 countries that submitted related data. Those who opened their clinics earned an average of $298,800, second only to Belgium ($337,931). https://www.koreabiomed.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=21966

Supporters believe more doctors will improve access in underserved areas and specialties. They note other developed countries have similarly increased medical school admissions.

As of June 2024, 66% of Koreans support the increase (source). Many view the strike as selfish and dangerous. The public sentiment boils down to:

“Just look at the data. We clearly don’t have enough doctors compared to other countries. Your poor grandparents in rural areas have to *travel* to get medical help for God’s sake! They make the most amount of money in Korea. Clearly there’s too much demand but not enough supply. We need to increase the number of doctors because healthcare is a public good and everyone deserves the best healthcare. These doctors that are on strike are arrogant, selfish assholes.”

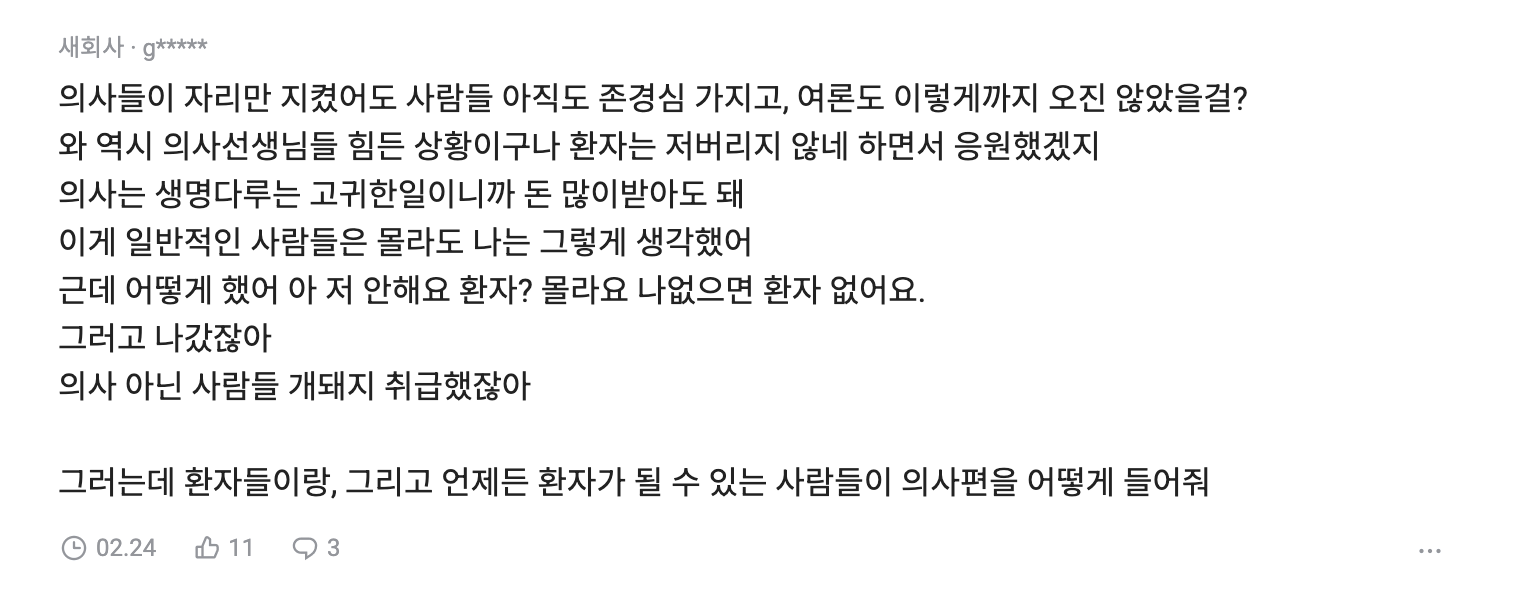

Some examples from online:

- “If doctors had just stayed at their posts, people would still have respect for them, and public opinion wouldn't have turned this bad, right? People would have cheered them on, thinking "Wow, doctors are really in a tough situation, but they're not abandoning patients." Since doctors deal with life, it's a noble profession, so it's okay for them to earn a lot. That's what I thought, even if most people didn't. But what did they do? "Oh, I'm not doing that." "Patients? I don't know." "Without me, there are no patients." That's how they left. They treated non-doctors like animals. So how can patients, and people who could become patients at any time, take the doctors' side?”

- “What doctors are protesting against... This is proof that the benefits given to doctors in our society are too great. The number of medical school students must be increased by more than two times.” (source)

Thesis: the legislation is terrible

The proposed legislation completely misses the point. It ignores the root causes of Korea's healthcare crisis and misreads the data.

Key issues the legislation ignores:

- Rural doctor shortage isn't about pay. Rural doctors earn good money.

- Essential specialty doctors are striking too. They're fed up with decades of government neglect.

- More medical students won't fix specialty shortages. The government sets all prices for insured procedures. Every Korean has insurance. Hospitals must accept these government-set prices.

The real story is complicated:

Korea's universal healthcare launched in 1989 with rock-bottom prices to make care affordable for everyone. Well-meaning policies to "help the poor" backfired spectacularly. They created massive demand for big city hospitals while prices for insured procedures lagged behind inflation for decades. Essential specialties got hit hardest.

Hospitals survive by pushing uninsured treatments or pivoting to profitable fields like dermatology and plastic surgery. Since the government controls prices for essential care, hospital funding depends entirely on the national insurance budget.

Why are prices so low? Simple: Koreans don't pay enough healthcare taxes. The median household contributes just 3.5% of income to healthcare-33% less than Japan and two to three times less than Norway or the UK.

Yet Korea maintains excellent healthcare quality and access. How? The country's brightest students become doctors by default. Unlike other developed nations, Korea offers few alternatives in research, entrepreneurship, or finance.

These two factors-inadequate healthcare funding and top talent concentration in medicine-are the real problems. Simply adding more doctors won't fix decades of systemic failure propped up by the sacrifices of Korea's intellectual elite.

Background

South Korea's healthcare system began with the Medical Insurance Act of 1963 under Park Chung-hee's military government. The law flopped-it relied on voluntary participation with no government funding.

Healthcare access in the 1960s and early 1970s was abysmal. A 1972 survey found only 27% of Seoul residents, 18% of other urban residents, and 2-3% of rural residents got medical care. Everyone paid out-of-pocket for 90% of costs. By 1974, 40% of sick people nationwide avoided medical services entirely. In rural areas, 43% couldn't afford treatment.

Park's government chose economic development and defense over healthcare. In 1965, health spending was just 0.1% of the budget-less than Vietnam (0.6%) or India (0.7%). By 1970, all health-related ministries combined got only 6% of the budget.

This neglect created a private-dominated system. By 1974, private providers controlled 82% of doctors and 79% of hospital beds. Medical costs exploded, rising three times faster than living costs from 1965 to 1975.

The turning point came in the mid-1970s:

- Social unrest exploded after patients died when hospitals refused treatment over money.

- Intelligence agencies warned that healthcare inequality threatened national security.

- Large hospitals needed steady revenue streams to sustain growth.

- Major corporations started viewing health insurance as social responsibility.

Korea's healthcare pricing system started in 1976 when the government began creating national health insurance. Officials set prices for 413 medical items at 20% below market rates to make healthcare affordable. Doctors protested immediately.

The government studied 11 major hospitals including Seoul National University Hospital and Yonsei Medical Center. They found medical income broke down as: 47% technical fees, 1.5% consultation fees, 33% medication/injection fees, and 18% hospitalization fees. Officials claimed they set prices at 75% of market rates, expecting higher patient volumes to compensate.

The Korean Medical Association disagreed. They insisted actual rates were only 55% of market prices, especially at Seoul's general hospitals. The government countered that location-based adjustments and medication costs brought rates near the 75% target. This dispute set the pattern for decades of conflict.

Mandatory health insurance rolled out gradually starting in 1977:

- 1977: Companies with 500+ employees

- 1979: Companies with 300+ employees

- 1981: Companies with 100+ employees

- 1988: Rural areas and companies with 5+ employees

- 1989: Urban self-employed

Public sector workers got separate coverage:

- 1979: Government employees and private school teachers

- 1980: Military personnel

The cornerstone of mandatory health insurance was the 당연지정제 (automatic designation system). This policy legally requires every medical institution in South Korea to become a National Health Insurance provider. All facilities must treat NHI patients and accept government-set prices.

The government created this system because Korea had almost no public hospitals. They forced private institutions to participate. Economists compare it to the interest rate freeze of August 3, 1972-an intervention "impossible under normal market conditions." South Korea remains the only country that legally mandates all medical institutions to join national health insurance. This law strips Korean hospitals of any pricing power.

Healthcare providers barely resisted these policies for several reasons. Coverage wasn't universal-many patients still paid out-of-pocket. The 180-day annual coverage limit softened the financial blow. Gradual implementation gave doctors time to adapt without immediate severe losses.

The automatic designation system emerged under Park Chung-hee's authoritarian regime. Open opposition meant political and social suicide. Doctors had no real choice but to comply.

Aside: Many doctors genuinely supported expanding healthcare access. The Blue Cross movement, started by Dr. Jang Ki-ryeo in Busan in 1968, proved doctors recognized the value of inclusive healthcare. This grassroots insurance scheme spread to other cities, showing medical professionals would voluntarily participate in cooperative systems. These successful experiments made government mandates easier to accept-doctors had already seen the benefits for public health. Political pressure combined with genuine belief in the mission led most doctors to accept the system despite financial concerns.

By 1989, South Korea achieved universal health coverage-94.2% of the population had insurance. But the system remained fragmented across numerous insurance societies, creating financial imbalances and coverage gaps between regions and job types.

President Kim Dae-jung completed the system. Despite opposition from financially healthy workplace insurance funds, Kim merged all insurance societies into a single National Health Insurance Corporation in 2000. Coverage expanded to 365 days in 2002.

This evolution from low 1976 prices to universal coverage blessed patients with affordable care. For providers, it marked the beginning of a slow-motion collapse.

Accessibility and quality metrics

How good was Korea's healthcare before the strike? Let's examine key metrics comparing South Korea to other developed nations:

- Mortality rates (cancer, infant, maternal)

- Cancer survival rates

- 30-day hospital readmission rates

- Specialist-to-physician ratios

- Appointment wait times

- Urban vs. rural physician distribution

- Preventable mortality rates

I'll explain why each metric matters and show comparative data from Korea, the US, UK, Japan, and others. Spoiler: Korea often beats or matches other developed nations.

Mortality rates

Mortality rates offer an objective healthcare quality measure-death is unambiguous. They reflect preventive care, treatment effectiveness, and emergency services. The limitations: they miss quality of life and non-fatal conditions, and different measures (infant, maternal, age-specific) paint different pictures. The data:

- Cancer mortality rate

- Infant mortality rate

- Maternal mortality rate

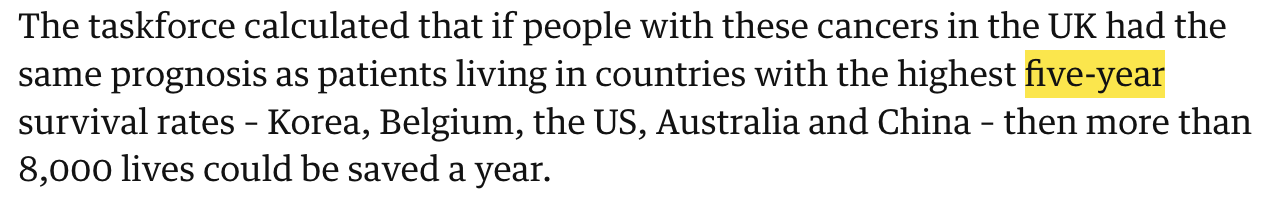

Cancer survival rates

Korea has among the world's highest five-year cancer survival rates.

Cancer survival rates reveal healthcare quality. High rates mean better treatment access and quality, effective screening programs, early diagnosis, and overall healthcare accessibility.

- Korea(including remission rates): 72.1% (source)

- US: 69% (source)

- UK: 55.7% (source)

- Japan: 66.2% (source)

30-day readmission rate

The 30-day readmission rate matters because:

- Care quality: High rates suggest inadequate treatment, premature discharge, or poor coordination.

- Patient impact: Readmissions harm health, quality of life, and trust in healthcare.

- Continuity: Shows how well hospitals prepare patients for discharge and coordinate follow-up.

- Performance benchmark: Healthcare systems worldwide use this to evaluate hospitals.

High ratio of specialist to physicians

Korea has an unusually high specialist ratio compared to any other nation. Here's the ratio of specialists to total physicians across OECD countries:

- US: 56.8% (562,705 / 989,320) (source)

- UK: 28.9% (110,079 / 380,352) (source)

- Norway: 55.5% (15,502 / 27,924) (source)

- Belgium: 62.8% (23,552 / 37,504) (source, source)

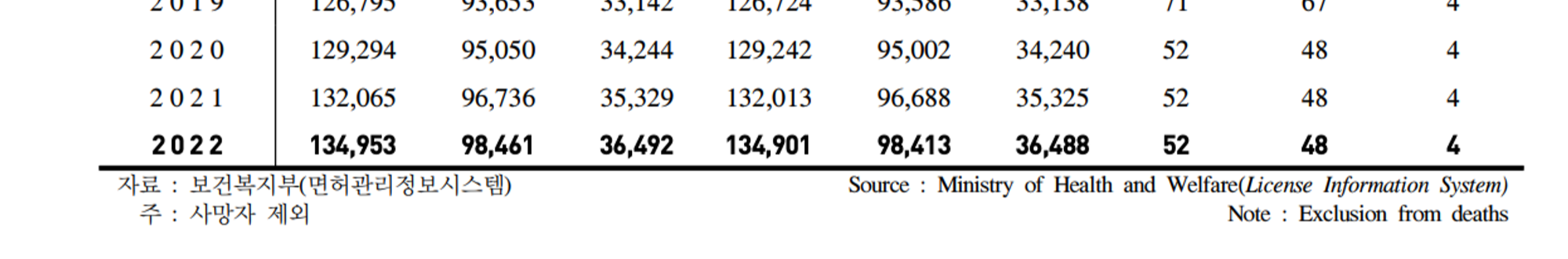

- Korea: 80.5% (108,697 / 134,953)

Ministry of Health and Welfare (License Information System).

Low appointment wait times

Korean patients can see specialists directly without primary care referrals. 51.3% walk into tertiary hospitals and get examined immediately (source).

At Korea's "big 5" hospitals:

- 16.3% see their chosen specialist same day

- 20.7% within a week

- 18.4% within two weeks

- 17.6% within a month

75% see their specialist of choice within a month. At general hospitals (100-300 beds), 90% wait less than two weeks. Expat websites confirm this speed is unheard of elsewhere (link1, link2).

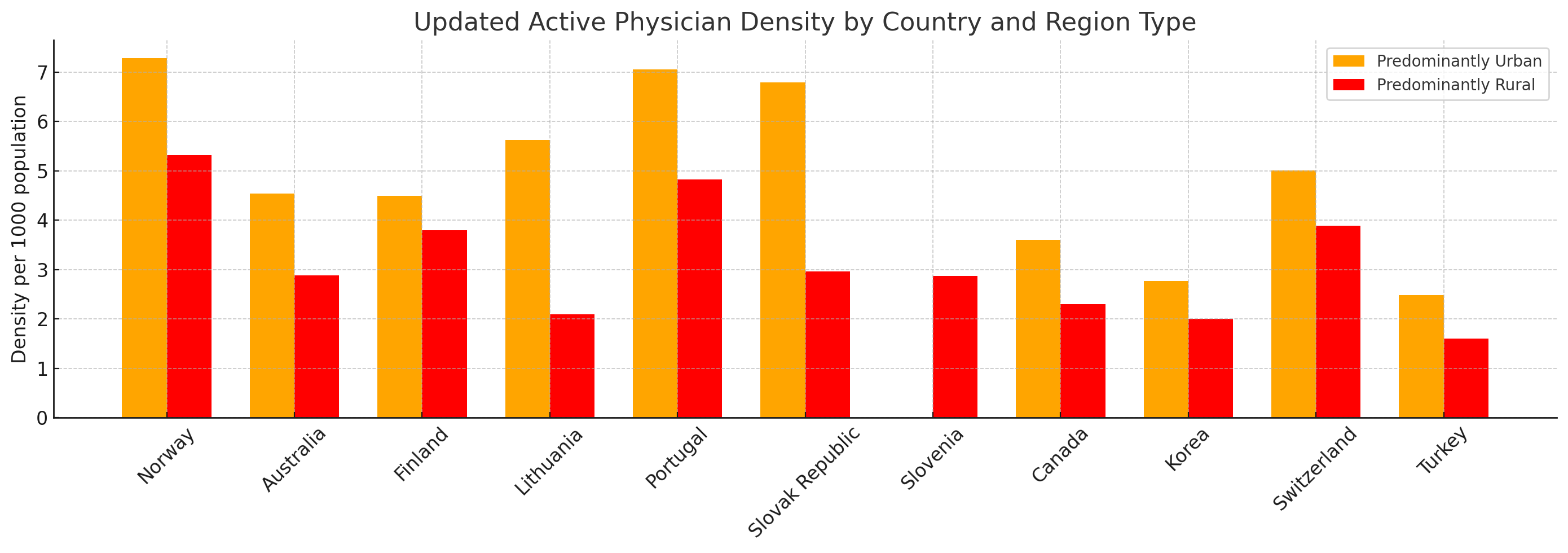

Similar number of physicians between rural and urban areas

Contrary to popular belief, Korea has minimal urban-rural disparity in doctor access. OECD data shows Korea has 2.77 physicians per 1,000 in urban areas versus 2.0 in rural areas (2021). Only Switzerland and Norway do slightly better.

OECD Regional social and environmental indicators, 2021.

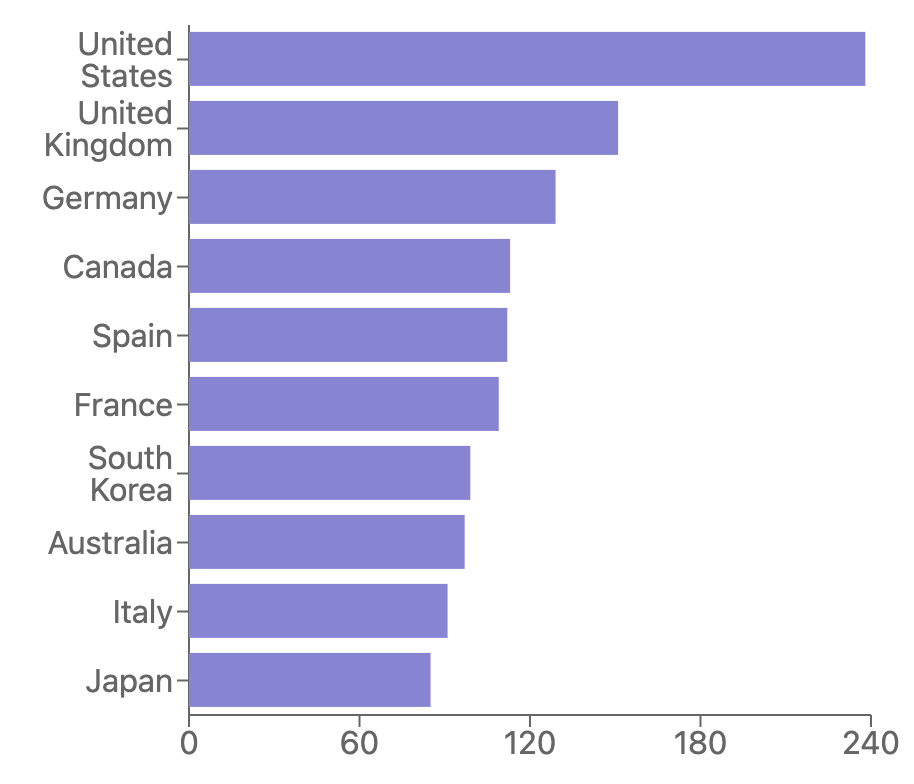

Low preventable mortality

Preventable mortality measures deaths that timely healthcare or public health measures could have avoided. These include treatable cancers, cardiovascular diseases, infections, and injuries.

Key aspects:

- Scope: Deaths from preventable or treatable conditions

- Age focus: Premature deaths before age 75

- Time-sensitive: Tests healthcare's ability to intervene quickly

Korea ranks 8th in OECD with 99 deaths per 100,000. Only seven countries do better: Israel (83), Japan (85), Italy (91), Iceland (93), Switzerland (94), Sweden (97), and Australia (97). Compare that to France (109), Canada (113), Germany (129), UK (151), and US (238).

Mortality rates from preventable causes in OECD countries in 2021.

This data debunks the ambulance transfer panic. Deaths from transfers would show up in these numbers. Korea's preventable death rate remains excellent despite all the problems driving doctors from emergency medicine and other essential specialties.

Korean doctors deliver world-class outcomes. Healthcare access-proximity, speed, and price-has no global parallel.

Strain on the system: Prices

Korean healthcare is too cheap. The fee schedule hasn't kept pace with inflation.

Korean hospital fees are 2 to 100 times cheaper than US prices. Example: The surgical component of a C-section costs $345.52 in Korea. The entire procedure costs $2,487.50. Compare that to the UK (3,806 euros for surgery alone) or the US ($987.77 for Medicare code 59514, with average total payments of $18,570).

What is a fee schedule?

A fee schedule lists preset prices insurance pays hospitals for medical services. In Korea, the government sets these prices through the National Health Insurance Service.

Forget out-of-pocket costs-that's not the issue. We're examining what hospitals actually receive for their labor, facilities, and materials.

Example: One country bills $10,000 for a procedure. Insurance covers $9,900, you pay $100. Another country bills $150. Insurance covers $100, you pay $50. Patients see similar costs, but hospitals face vastly different economics.

The government unilaterally sets all prices for insured procedures. Hospitals have zero control. The prices are absurdly low.

For common procedures like cataract surgery or C-sections, Korea uses diagnosis-related groups (DRGs)-bundled pricing for all related procedures, tests, and diagnoses. These public prices show exactly what hospitals receive for everything involved.

DRG prices include all costs: pre-op testing, the surgery, post-op care, everything. US average payment amounts often exclude these extras. The best US comparison is cash prices, which quote all-inclusive costs.

DRG procedures must charge exactly the DRG price. No exceptions.

I'll normalize prices using GDP per capita PPP:

2022 GDP per capita (PPP) (source)

- Korea: $53,759.58

- US: $77,191.87

Ratio: 1:1.43

I'll multiply Korean prices by 1.43 to adjust for GDP differences.

Note: I'm using Medicare prices for the US-already much cheaper than private insurance. US doctors earn multiples above these Medicare rates.

Concrete examples

Emergency room visit

ER costs matter because:

- Access: High costs deter necessary care, worsening outcomes. Low costs improve access for vulnerable populations.

- System efficiency: Excessive ER costs signal problems:

- Overuse for non-urgent care

- Lack of affordable primary care

- Insufficient prevention

US

- CPT code 99284

- Fee schedule amount: ~$130.61

- Cash price: $699.00

Korea

- Fee schedule amount: $29.96 (41540)

V2200,2024-01-01,응2가,응급**진료** 전문의 진찰료-권역응급의료센터,,1,0,0,41540

UK

- NHS tariff: $99.09 (91 euros)

VB11Z Emergency Medicine, No Investigation with No Significant Treatment 91 euros

Comparison

Normalized Korean price: $29.96 × 1.43 = $42.84

US costs 3x more.

Chest CT

Chest, abdomen, and pelvis CTs are the most common diagnostic scans. Prices with or without contrast are similar.

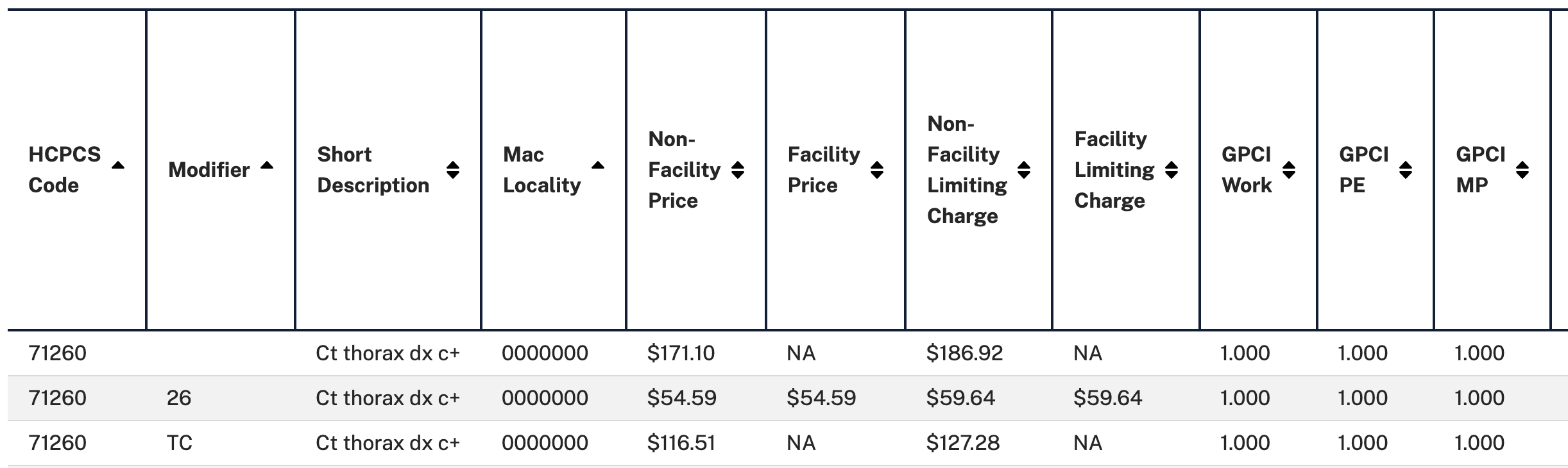

US

-

CPT code 71260

-

Fee schedule amount: ~$177.08

- Make sure to not use the ones with just 26 or TC (source). The Korean price comparison includes both because there’s almost never a time when you take a CT but do not get a radiologist to look at it. A famous Korean healthcare administration professor named Kim Yoon, now part of the democratic party, makes the mistake of not understanding this difference in his price calculation when looking at the CMS data (source).

- Make sure to not use the ones with just 26 or TC (source). The Korean price comparison includes both because there’s almost never a time when you take a CT but do not get a radiologist to look at it. A famous Korean healthcare administration professor named Kim Yoon, now part of the democratic party, makes the mistake of not understanding this difference in his price calculation when looking at the CMS data (source).

-

Average total payment amount: $175.06 or $228

-

Cash price: ~$2000

Korea

Chest CTs aren't always covered by insurance, so I include cash prices.

- Fee Schedule Amount: $74.95 (103,930 KRW)

HA464007,2024-01-01,다245라(2),일반전산화단층영상진단-흉부-조영제를사용하는경우,Chest CT-With Contrast Material,1,0,103930

UK

- NHS tariff: $80.57 (74 euros)

RD20A Computerised Tomography Scan of One Area, without Contrast, 19 years and over 74

Comparison

Normalized Korean price: $74.95 × 1.43 = $107.17

US costs 1.7-2x more.

Stroke

Korea desperately lacks vascular neurologists despite stroke being a leading hospitalization cause. Let's examine hospital payments for ischemic strokes (87% of all strokes).

Two main treatments:

- IV tPA (tissue plasminogen activator): Given within 3-4.5 hours to dissolve clots

- Mechanical thrombectomy: Physical clot removal via catheter, possible up to 24 hours later

Why IV-tPA is challenging:

- Diagnosis: Must distinguish ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke-tPA kills hemorrhagic stroke patients

- Risk assessment: Balance benefits against intracranial bleeding risk

- Patient selection: Multiple contraindications:

- Recent surgery/trauma

- Prior brain hemorrhage

- Uncontrolled blood pressure

- Anticoagulant use

- Dosing: Precise weight-based calculations required

- Monitoring: 24-hour intensive observation for complications

- Expertise: Requires neurologist or stroke specialist consultation

IV tPA

US

Korea

- TPA cost: $415.76 (625,071 KRW)

[드러그인포. (2024, August 8). 액티라제주사50mg(알-티피에이) ACTILYSE INJ. 50MG[RH-tissue-type plasminogen activator]. Retrieved August 8, 2024](https://www.druginfo.co.kr/detail/product_cp_cancer.aspx?pid=6351](https://www.druginfo.co.kr/detail/product_cp_cancer.aspx?pid=6351)

- Administering iv-TPA: $138.10 (source)

The $415 price isn't just the official rate-it's the full uninsured cash price. A doctor's post shows their guilt about charging even this "excessive" amount (source).

UK

- TPA cost: $326 (£300) (source)

- Administering iv-TPA: £1316

Result

Normalized tPA cost: $415.76 × 1.43 = $594.53 Normalized administration: $138.10 × 1.43 = $197.48

US costs 50-100x more for the complete procedure. The UK's tPA is cheap but administration costs are reasonable.

Mechanical Thrombectomy

US

- CPT Code 61645

- Fee Schedule Amount: CMS doesn’t provide the data for this.

- Average total payment amount: > $11500 (source)

Korea

- Fee Schedule Amount: $842.91 (1,160,620 KRW)

경피적혈전제거술-기계적혈전제거술[카테터법]-두개강내 혈관,Percutaneous Thrombus Removal-Mechanical thrombectomy(Intracranial vessel),1160620

UK

- Tariff: $12,793.75 (£11750) (source)

Result

US and UK cost at least 12x more.

Cataract

Korea's third most common surgery (source).

US

- CPT code 66984 - this is the code used for typical monofocal IOL cataract surgery.

- Average fee schedule amount: $602.37

- Average total payment amount: $2,220.35

- Cash price: ~$5000

Korea

- Fee Schedule Amount: $327.80 (453,980 KRW)

백내장및수정체수술-수정체낭외또는낭내적출술,Surgery for Cataract Or Lens-Extracapsular Or Intracapsular Extraction,2,9,453980

- DRG price for tertiary hospital (translated 상급병원: over 500 beds, over 20 medical departments, over 1 specialist for each medical department): $999.84 (1,374,880 KRW)

UK

- Fee Schedule Amount: $834.18 (£766)

BZ32B Intermediate, Cataract or Lens Procedures, with CC Score 0-1 - 766

Google "cataract surgery cost" in Korean and you'll find prices of $2,167-$2,890 (source). That's because patients choose premium multifocal IOLs not covered by insurance.

In the US, a multifocal IOL lens alone costs $2,000 in cheap areas. UCSF charges $4,000 per eye for multifocal surgery (source).

Comparison

Normalized Korean price: $327.80 × 1.43 = $468.75

The US fee schedule ($602.37) is higher, and average total payments ($2,220.35) are 5x more. Even the UK costs 1.5x more.

C-section

A C-section takes 45-60 minutes:

- Preparation: 15-20 minutes

- Baby delivery: 5-15 minutes after incision

- Placenta removal: 5-10 minutes

- Closing: 30-40 minutes

Emergencies can be done in 30 minutes.

The team includes 5-7 professionals:

- Obstetrician (surgeon)

- Assistant surgeon

- Anesthesiologist

- Scrub nurse

- Circulating nurse

- Pediatrician/neonatal nurse

- Additional support staff

US

- CPT Code 59514

- Fee Schedule Amount: ~$987.77

- Average total payment amount: $18570 (source)

- Cash price: ~$35907 (source)

Korea

- Fee Schedule Amount: $345.52 (475,750 KRW)

제왕절개만출술(1태아임신의경우)-초회(초산),Cesarean Section Delivery-First Fetus-Initial-Primiparous,475750

- DRG price for tertiary hospital: $2,487.50 (3,420,559 KRW)

UK

- NHS tariff: $4,144.58 (3806 euros)

NZ50C Planned Caesarean Section with CC Score 0-1: payment level 3

Comparison

Normalized Korean price: $345.52 × 1.43 = $494 Normalized DRG price: $2,487.50 × 1.43 = $3,557

US procedures cost 10x more than Korea. The fee schedule alone is 1.8x higher. The UK difference is equally shocking.

Korean prices are drastically lower than US prices and often beat the UK. Yet Korea's outcomes surpass the UK's and accessibility is unmatched.

Additional extra sources

- US Fee schedule

- US average total payment amount

- US Cash price

- UK Tariff workbook

- Korea Fee schedule

- https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1118dPFU_M7P-0MVXcJyMO9iShIjfbXPB_QzWdkZDV5A/edit?usp=sharing - for a given procedure, you can get the exact billed amount for the code. I suggest you download this as a csv and use grep to search through the content to explore for yourself.

- 2019 급여기준 및 심의사례집 https://www.hira.or.kr/ebooksc/ebook_560/ebook_560_201912300924568680.pdf

- Korea Average total payment amount

- For conditions under diagnosis-related groups (DRG) which are 7 different “treatments” that the government fix the absolute price on for the entire procedure including the facility fee, doctor fee, etc, we use https://www.hira.or.kr/rb/drg/drgAmtsList.do?pgmid=HIRAA030066050000 as a source.

- 2024 Korea DRG cost

Strain on the system: Structure

Low prices fuel a vicious cycle in Korean healthcare:

- Extreme patient volumes force doctors to prioritize quantity over quality

- Demand concentrates in big city tertiary hospitals

- Hospitals depend on uninsured procedures to survive

- Criminal prosecution rates for medical errors dwarf other countries

- Healthcare taxes remain paradoxically low-the median Korean pays just 7% of income

The result: a system that looks accessible and affordable but struggles to deliver sustainable, quality care across all specialties.

High patient volume

Undervalued medical time creates healthcare "shrinkflation." Doctors must see more patients in less time. Hospitals maximize revenue through volume. The fee schedule rewards patient turnover.

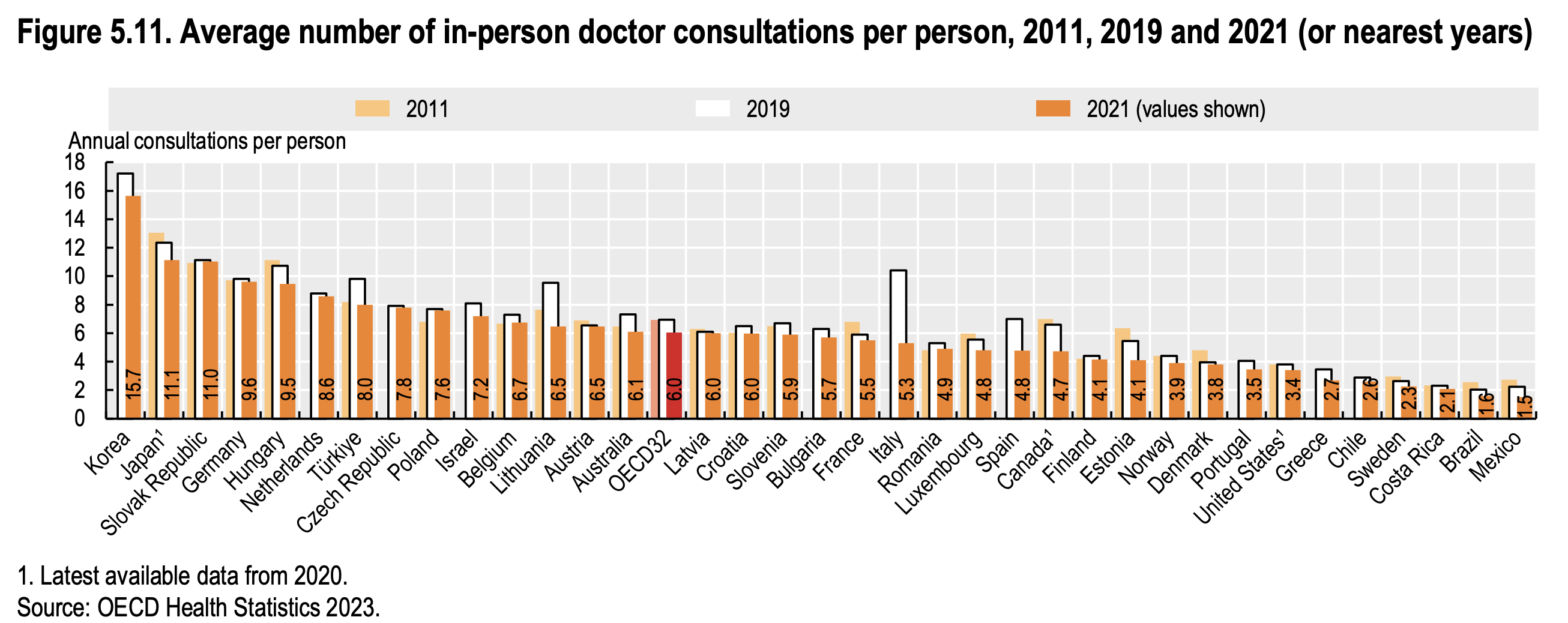

[OECD (2023). "Consultations with doctors". In Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.](https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/3a4927d8-en.pdf?expires=1721352973&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=B818F42A56EF3645A5AE443664D7E3E2#:~:text=In 2021%2C the average number,reporting between 4 and 10)

The statistics are staggering:

- 190,000 outpatients see doctors 150+ times yearly

- One 40-year-old visited 24 hospitals 2,050 times in 2021 (source)

- Koreans average 15.7 doctor visits annually versus:

- Japan: 11.1

- OECD: 6.0

- US: 3.4

Koreans call this "과다 의료" (excessive healthcare)-a symptom of systemic failure.

This explains why Korean patients get so little doctor time. Visit frequency and consultation length are inverse metrics. Hospitals push doctors to see maximum patients because prices are rock-bottom. Doctors meet quotas by rushing. Meanwhile, at ~$15 per visit, patients treat doctors like convenience stores.

A 2020 survey of 6,507 doctors confirms the crisis (source):

- Average daily load: 37.8 patients (34.2 outpatients + 3.6 surgeries)

- Doctors in their 50s: 40.6 patients daily

- Primary care clinics: 43.0 patients daily (highest)

- Most consultations: 6-10 minutes (36.7%)

- Follow-ups: 65.5% last under 5 minutes

- Metropolitan doctors see 36.1 patients daily vs. rural's 30.6

Centralization of demand to tertiary care

Tertiary hospitals face the worst patient overload.

Korea's 1989 medical delivery system was supposed to prevent hospital overcrowding through three tiers:

- Primary: Local clinics, health centers, hospitals <30 beds

- Secondary: Hospitals with 30-99 beds, general hospitals with 100-299 beds

- Tertiary: University hospitals, specialized facilities with 500+ beds (700+ for non-university)

The plan: patients start at primary care, get referred up when necessary.

Medical service areas

The original system included "medical service areas" (권역 진료의뢰제도) to balance regional development and prevent urban concentration. Korea had 138 medium zones and 8 large zones. Patients had to stay within their designated area.

In 1998, President Kim Dae-jung's democratic party scrapped these restrictions (source). Rural patients could now flood Seoul hospitals.

Special consultation fee

The "선택진료" (selective treatment) system started in 1967, letting patients pay extra for experienced doctors. By 1991, the government standardized it: patients could pay 15-50% more to see top specialists (source).

That 50% sounds significant until you realize it meant $10-15 extra. The price gap between Korea's best and worst doctors was the cost of lunch. Yet people complained endlessly-a testament to populist propaganda.

President Moon Jae-in's democratic party killed the system entirely on January 1, 2018, ending 28 years of formalized doctor choice.

The democratic party systematically dismantled every incentive supporting the tiered medical system-all in the name of "better coverage." Nothing stops patients from bypassing primary care entirely.

Removing tertiary care barriers crushed smaller hospitals while overwhelming the giants.

The statistics prove it:

2018: Large hospitals' expenses jumped 19.8% to 26.6 trillion won-the biggest increase since 2003. Market share rose from 32% to 34.3%. Local clinics dropped from 28.3% to 27.5%. Financial pressure kills 1,200-1,300 local clinics annually (source).

2023: Tertiary hospitals' share of medical costs hit an all-time high of 19.8%, up from 16.8% in 2022. Of 45 tertiary hospitals, 28 cluster in Seoul-including Seoul National University Hospital, Samsung Medical Center, Asan Medical Center, and Severance (source).

Rural Korea has comparable physician density to urban areas. Yet people avoid rural hospitals. The problem isn't doctor shortage-it's demand shortage. Adding doctors won't fix urban-rural disparities.

Rural doctors earn excellent money, just like in the US where rural pay exceeds urban. But in Korea, it's a death spiral: bad policies kill demand → hospitals can't afford quality staff and equipment → care quality drops → demand drops further.

A rural doctor confirms this reality. Dr. Hwang in Miryang, South Gyeongsang Province, shares his five-year experience (link):

- 8% decline from 2022 to 2023

- 20% fewer patients, 28% less revenue in early 2024

- 10% annual decline over five years

His conclusion: Rural areas don't lack doctors-they lack people. Houses stand empty.

Who will fund hospitals, equipment, and staff when everyone travels to Seoul for care?

Procedures uninsured by healthcare

Despite universal healthcare, Korea has a massive private insurance market covering out-of-pocket expenses and uninsured procedures (비급여, "non-covered items").

Non-covered items include:

- Vision correction (LASIK, LASEK)

- Dental prosthetics (gold crowns)

- Manual therapy

- Medical certificates

- Some ultrasounds, MRIs, and fertility treatments (context-dependent)

Hospitals set their own prices for these items. Patients pay full cost.

72.6% of Koreans have private insurance (source).

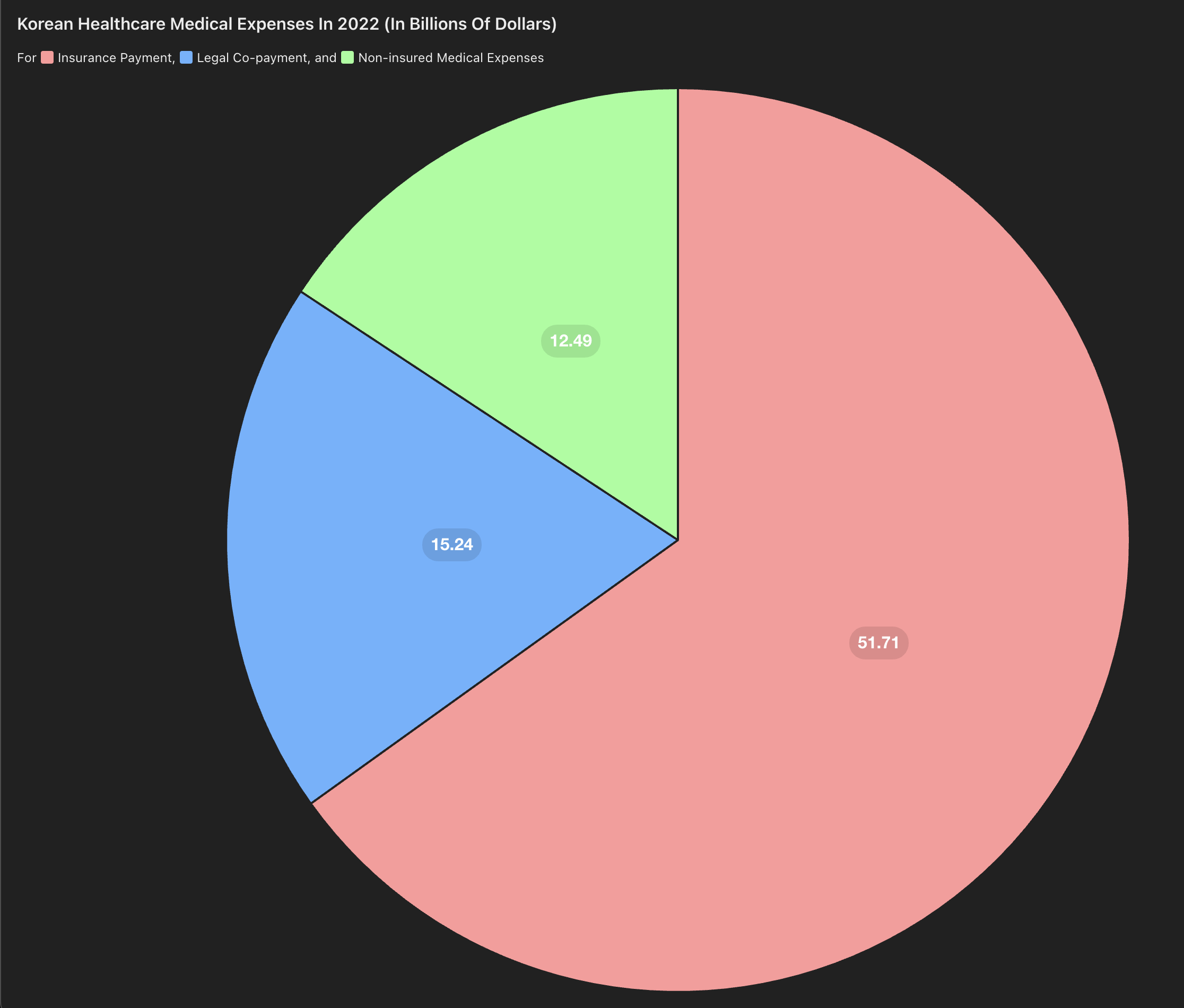

2022 total medical costs: 111.1 trillion won ($80.23B)

- Government pays: 71.6 trillion won ($51.71B) = 64.4%

- Legal out-of-pocket: 22.1 trillion won ($15.23B) = 19%

- Non-covered items: 17.3 trillion won ($12.49B) = 15.5%

[이정환. (2023, January 10). 작년 보장률 64.5%...0.8%p 하락 "비급여 관리". 데일리팜](https://www.dailypharm.com/Users/News/NewsView.html?ID=295932](https://www.dailypharm.com/Users/News/NewsView.html?ID=295932)

Democratic party politicians cite high uninsured costs as proof the system is broken. They focus on "건강보험 보장률" (healthcare coverage rate)-Korea's 64.4% versus OECD's 76.3%. Their solution: expand coverage (source). I'll address this argument next.

Regarding this, Nam In-soon emphasized, "According to the NHIS, while 46.64 million people benefited from Moon Jae-in Care by the end of last year, with medical expense reductions amounting to 26.4912 trillion won, the coverage rate decreased by 0.8 percentage points to 64.5% in 2021 compared to the previous year. However, this is judged to be due to an increase in non-covered services at clinics. The coverage rate for hospitals above the general hospital level in 2021 was 69.1%, and for the four major severe diseases, it continuously increased to 84.0% in 2021." She stressed, "We must continue to promote the strengthening of health insurance coverage while further enhancing the management of non-covered services to alleviate the medical expense burden on the public." Source: https://www.akomnews.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=news&wr_id=55286

Korea's 15.5% non-covered spending exceeds international norms. The UK's private healthcare spending was 13.8% in 2023 (£40 billion), with voluntary insurance just 2.5% (£7 billion) (source).

Hospitals rely on high patient volume + non-covered items to survive

Two questions remain:

- How do hospitals profit with such low prices?

- How do they stay operational?

The answer: hospitals can't survive without non-covered items. Let's examine the finances.

| Hospital Name | Total Revenue (in $ million) | Total Expenses (in $ million) | Profit Before Tax (in $ million) | Reserve for Inherent Business Purpose (in $ million) | Reversal of Reserve (in $ million) | Net Profit (in $ million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samsung Seoul Hospital | 3,133 | 3,210 | -77.2 | 0 | 4 | -73.3 |

| Severance Hospital | 3,261 | 3,026 | 222.7 | 269.8 | 0 | -47.1 |

| Asan Medical Center | 4,035 | 3,894 | 141.2 | 118.4 | 0 | 22.7 |

| Bundang Seoul National University Hospital | 1,746 | 1,674 | 71.3 | 89.4 | 36.3 | 16.3 |

| Seoul National University Hospital | 2,645 | 2,618 | 26.5 | 40.3 | 15.1 | -1.2 |

The table shows major Korean hospitals' finances from 2017-2019 (source). Democratic party congressman Go Young-in investigated these university hospitals, claiming they dodge taxes by reserving "substantial" pre-tax profits as funds for business purposes.

This is absurd. These "substantial" profits are razor-thin margins that would terrify any business owner. Single-digit percentages. The accounting practice is standard for non-profits. Calling hospitals greedy for maintaining emergency reserves is like blaming squirrels for storing nuts.

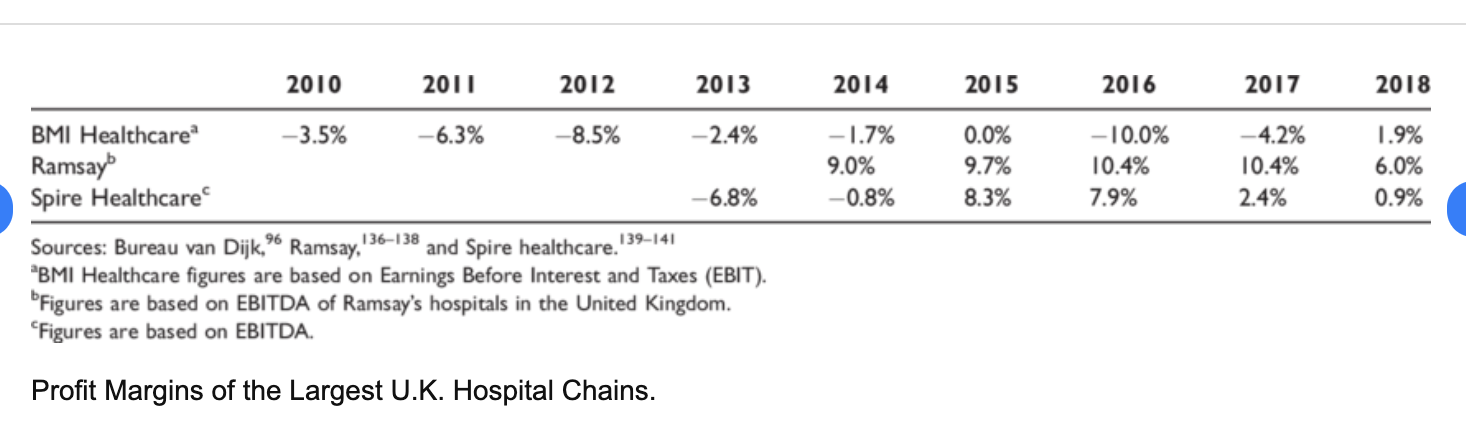

On paper-thin margins

The margins are laughable:

- Samsung hospital: unprofitable

- Severance: 6%

- Asan: 3%

- Bundang SNU Hospital: 4%

- SNU Hospital: 1%

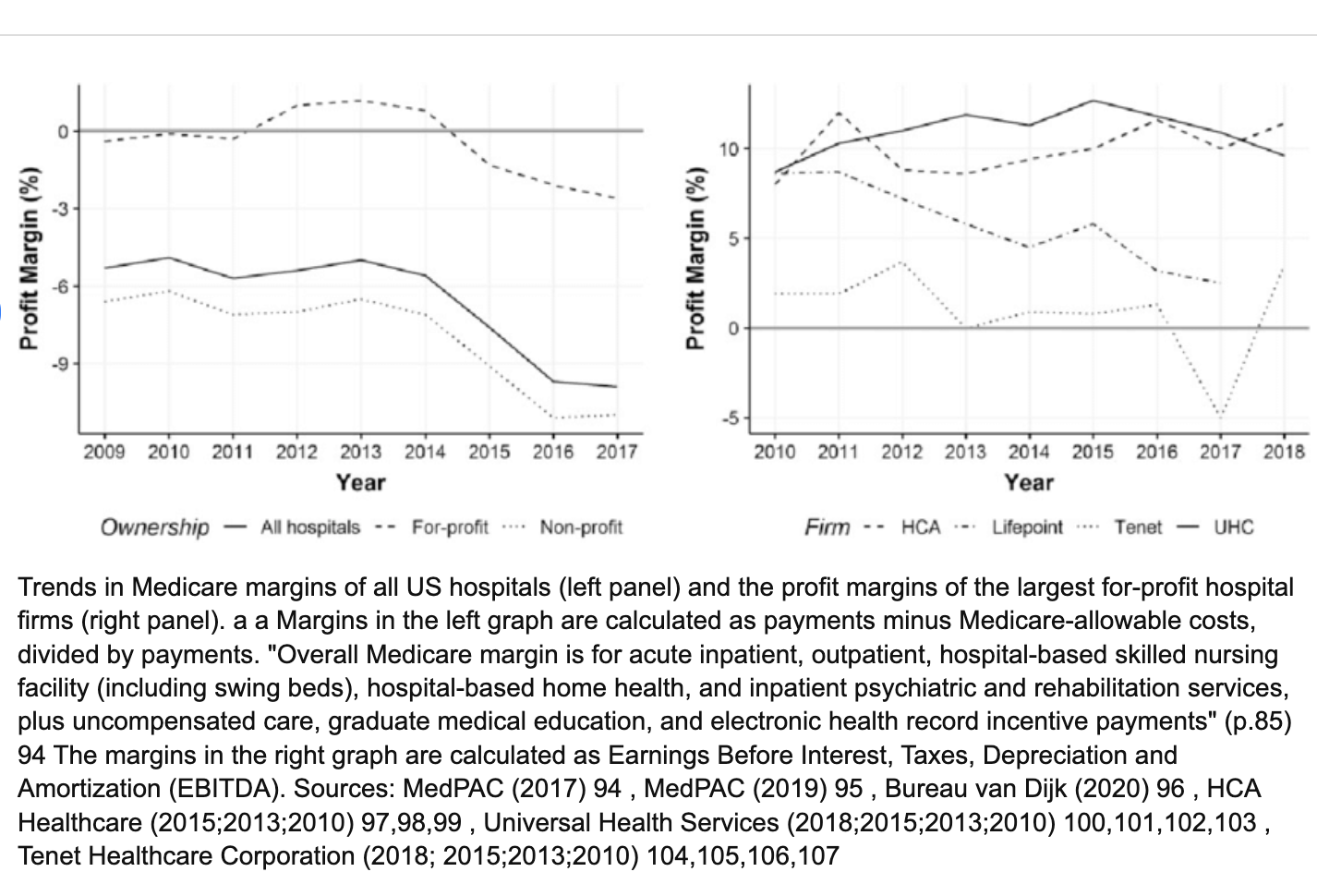

A 2015 survey of 3,200 hospitals reveals the crisis (source):

- Overall average: 1.9%

- Tertiary hospitals: -0.3% (losing money)

- General hospitals 300+ beds: 1.4%

- General hospitals 160-299 beds: 4.2%

- General hospitals <160 beds: 3.5%

- Hospital-level institutions: 2%

- Psychiatric hospitals: 8.8% (only profitable sector)

Calling these hospitals "greedy capitalists evading taxes" is ideological nonsense. Their margins match global standards: Stanford Health (5.3%), Mayo Clinic (6%), US average (~3%) (source).

Fitch Ratings states hospitals need 3% margins minimum to meet obligations (source).

On reserved funds

"고유목적사업준비금" (Reserved Funds for Specific Purposes) are emergency funds for financial crises. Hospitals deduct these as expenses, lowering taxes while maintaining competitiveness through investments in facilities, equipment, education, and research.

Strict rules prevent abuse: Reserves must be used within five years for designated purposes or face penalties. Payroll and general operations are forbidden without special permission (source, source).

Spending reserves on immediate needs would gut future development and research, degrading medical education and care quality.

Korean hospitals share single-digit margins with global peers but operate completely differently.

We've seen the patient volume crisis. Here's another angle-revenue breakdown for Korea's big-5 hospitals:

이지현. (2020, October 6). 외래수익으로 확연히 드러난 빅5 쏠림...."정부 정책 패착". 메디칼타임즈.

US hospitals typically get 60% revenue from inpatients, 40% from outpatients (source).

Korean hospitals achieve similar ratios only by seeing 4.5x more patients. Visits are so cheap that hospitals must process massive volumes to survive.

The second survival strategy: non-covered procedures.

With insured prices below sustainability, specialists abandon their training:

- 50% of Gangnam plastic surgery clinics are run by non-plastic surgeons. 1,000 of 6,000 general surgeons hide their specialty (source).

- Between 2018-2022, general practitioners opened 979 new clinics. 86% (843 clinics) claim to provide dermatology services (source).

Local clinics thrive while tertiary hospitals struggle-clinics don't support money-losing essential specialties.

- Local clinics: 25% of outpatient revenue from non-covered items (8.6T won / $6.2B)

- General/tertiary hospitals: 8.2% from non-covered items (4.2T won / $3.03B)

전영선. (2023, January 16). [1000호 특집] 연도별 전국 의원급 의료기관의 경영상황 분석. 치과신문.

- The pay gap between tertiary and primary care is massive:

| University Hospital | Full-time Professor (USD) | Contract Doctor (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Kangwon National | $71,200 | $102,800 |

| Kyungpook National | $104,000 | $104,800 |

| Gyeongsang National | $105,300 | $184,500 |

| Pusan National | $118,400 | $121,000 |

| Seoul National | $77,300 | $144,100 |

| Chonnam National | $96,300 | $117,400 |

| Jeonbuk National | $91,600 | $106,400 |

| Jeju National | $93,900 | $126,600 |

| Chungnam National | $101,800 | $126,300 |

| Chungbuk National | $78,000 | $96,600 |

Not all doctors are equal. Primary care differs from tertiary care. Essential specialists differ from dermatologists and plastic surgeons. This isn't moral judgment-it's economics. Without non-covered items, hospitals die.

Prevalence and ease of criminal lawsuits

Korea's justice system treats medical errors as crimes, driving doctors from essential specialties.

Liberals deflect with stories of criminal doctors-hidden cameras in pediatrics (source), OB/GYN molestation (source). Yes, prosecute actual crimes. But we're discussing "업무상 과실치사" (death by occupational negligence)-medical errors.

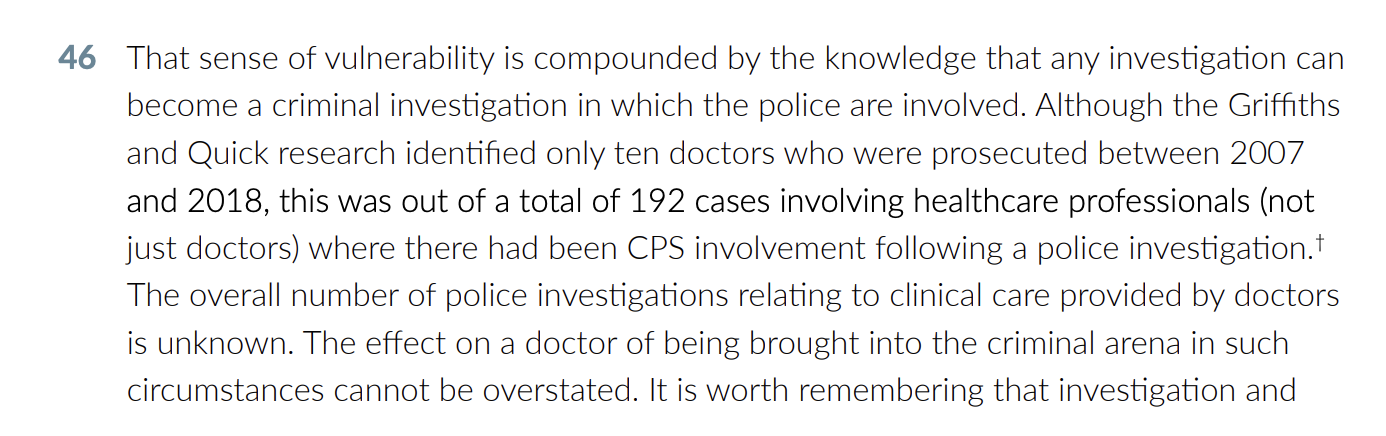

Korea charges 0.5% of doctors annually for occupational negligence deaths. Japan: 0.01%. That's 755 of 140,000 Korean doctors versus 52 of 407,000 Japanese doctors (source).

Trial outcomes:

- Korea: 354 trials over 11 years → 239 guilty

- Japan: 202 trials over 18 years → 32 guilty

Germany prosecutes just 4.2% of 4,450 forensic medical reports as negligent deaths (source).

The UK had 192 cases over 9 years. Only 10 prosecutions.

Japan actively reduced prosecutions:

- 1999-2010: 22.6% prosecution rate

- 2011-2015: 6.5% prosecution rate

How should we define medical negligence?

UK law makes medical negligence criminal only in extreme cases (source):

- Deliberate harm: Murder or intentional attacks (e.g., Beverley Allitt, Harold Shipman)

- Safety violations: Breaching regulations like the Health and Social Care Act 2008

- No consent: Procedures without informed consent (battery/assault)

- Gross negligence manslaughter: "Truly, exceptionally bad" care causing death. Requires:

- Duty of care existed

- Breach of duty

- Breach caused death

- Breach so serious it's criminal

- Corporate manslaughter: Organizations liable for gross negligence deaths

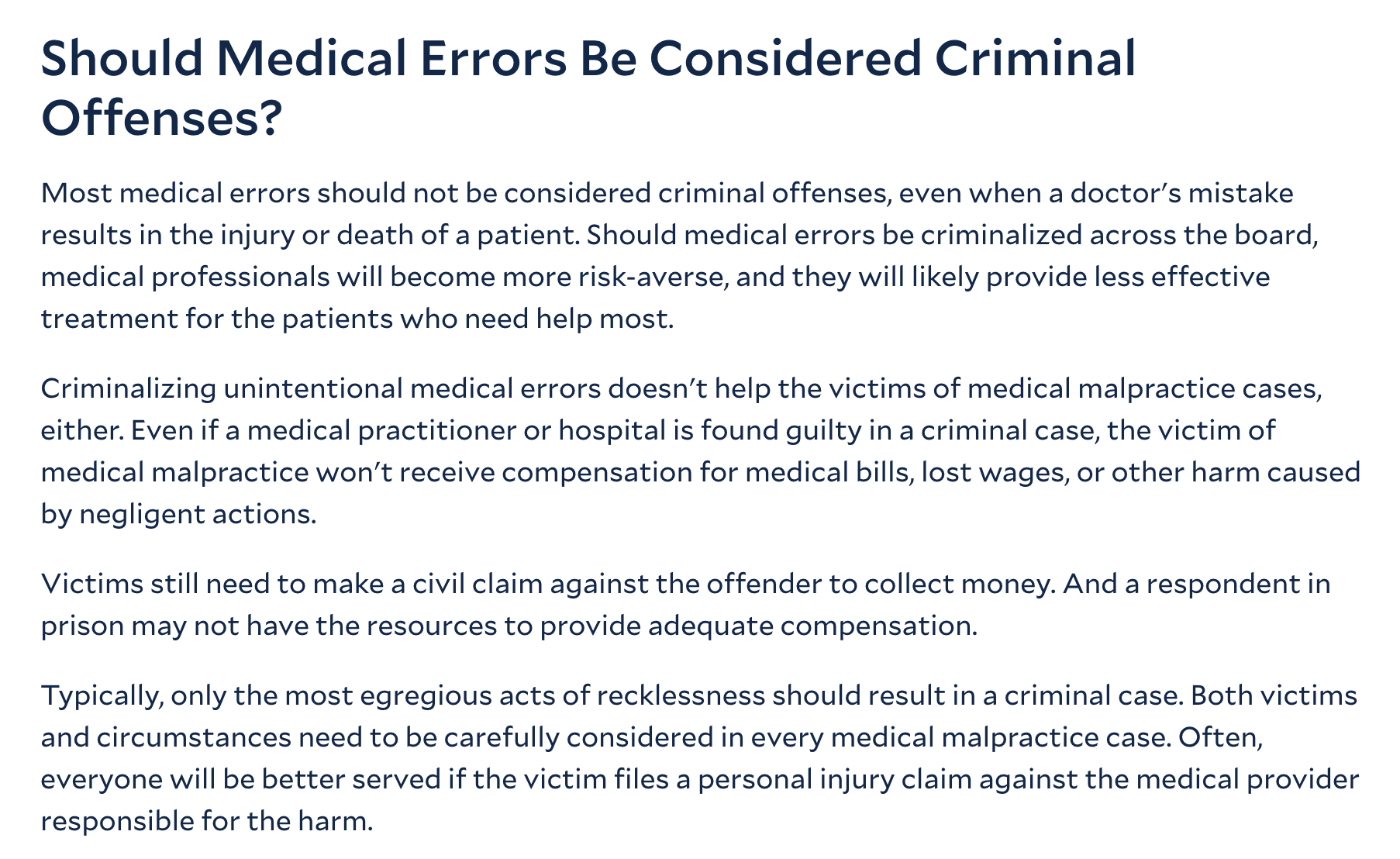

US law treats medical malpractice as civil in "nearly all circumstances" (source). Criminal charges require extreme deviation:

- Healthcare fraud: Financial motives over patient care (kickbacks, false billing)

- Intentional harm: Deliberate injury (rare, includes assisted suicide)

- Unlicensed practice: Operating without qualifications

- Gross negligence: Treating while impaired, denying obvious life-saving care

Fuchsberg, Alan. "Is Medical Malpractice a Criminal Act?" Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Firm, 20 July 2016.

What are examples of cases in Korea?

Judge for yourself if these warrant criminal prosecution:

Case 1: Mother dies during stillbirth (source)

2019, Andong clinic. Woman bleeds to death delivering stillborn baby.

Verdict: Doctor gets 8 months prison. Nurse gets 8 months suspended.

Court's reasoning: Should have checked vitals at 6 PM to detect placental abruption, preventing death.

Medical community response: "Armchair criticism." Hidden placental abruption is unpredictable. Ultrasounds aren't done during stillbirth deliveries.

Case 2: Four NICU deaths at Ewha Hospital (source)

- Four newborns die within 80 minutes. Staff charged with negligent homicide.

Verdict: Not guilty at all three court levels after 5 years.

Why acquitted:

- No proof SMOFlipid supplement was contaminated

- Bacteria-positive syringe found in trash (possible post-disposal contamination)

- Not all victims had same infection

- One twin survived without bacteria

- Dividing medications isn't illegal with proper infection control

Case 3: Delayed bowel surgery (source)

- 54-year-old with bowel obstruction. Patient chose conservative treatment for economic reasons.

Timeline:

- Days 1-7: Headaches, fever, bloody stools. Doctor continues antibiotics.

- Day 8: Emergency surgery removes 80cm dead intestine.

- Result: Sepsis, kidney failure, permanent kidney damage.

Verdict: 6 months prison, suspended 2 years.

Court's reasoning: Should have operated earlier when symptoms worsened.

Medical experts: Closed loop obstruction requires aggressive monitoring and early intervention.

Does your opinion matter?

No. The reality: excessive lawsuits + perceived threat = doctors flee essential specialties. These specialties are already the hardest-legal threats make them unbearable.

Root causes of the strains

Low Tax Rates

Korean healthcare is cheap because Koreans pay almost nothing in healthcare taxes compared to other universal systems.

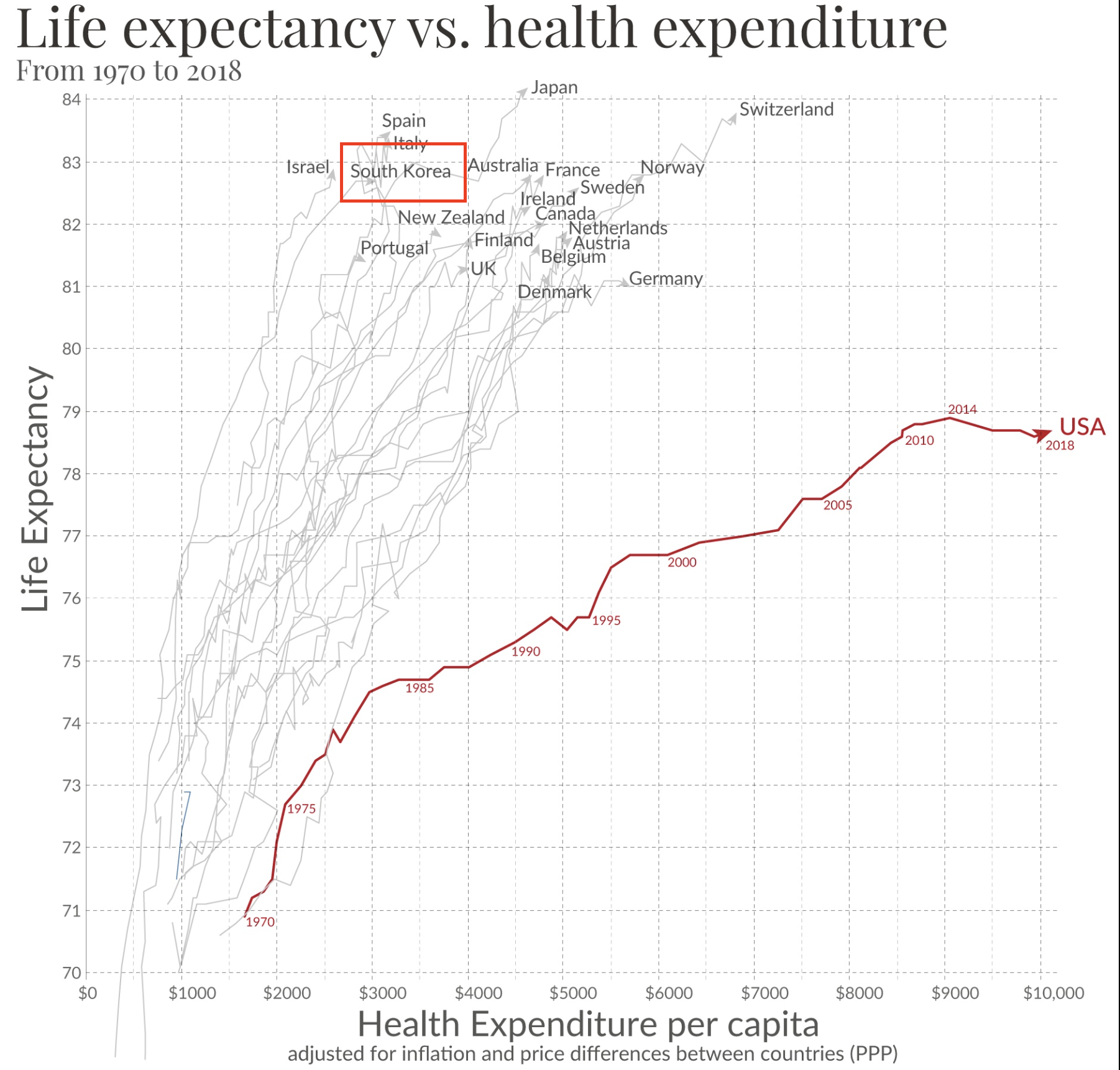

Top-down perspective

Total health expenditure tells the story:

Korea spends a fraction of what other countries spend.

Bottoms-up perspective

Let's examine actual tax rates:

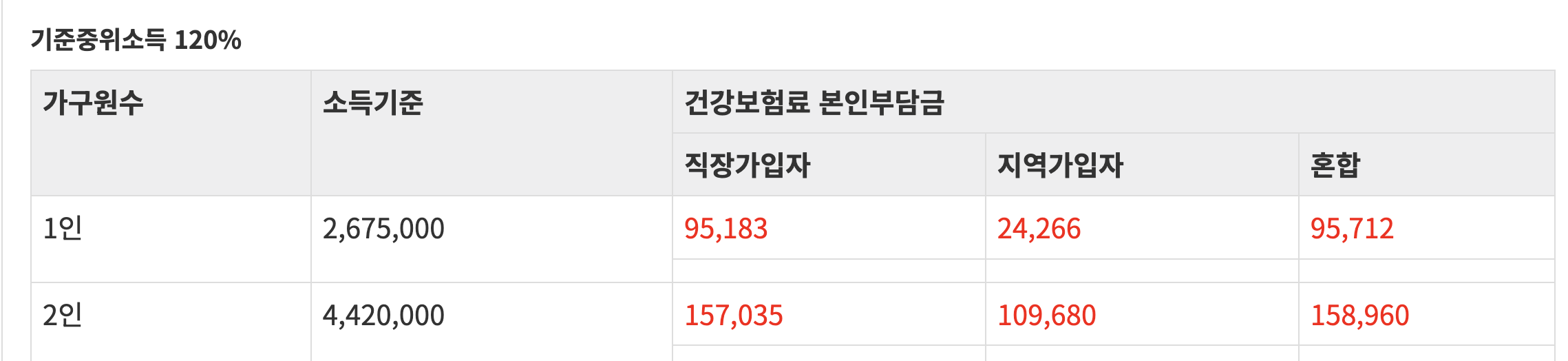

Korea: 7%

The median Korean pays just 7% of income for healthcare. For someone earning 120% of median income (2,675,000 won/month), that's 95,712 won-roughly 3.5% from the employee, 3.5% from the employer.

Koreans, without fully realizing it, benefit from significantly reduced medical costs thanks to the wealthy. The basic monthly health insurance premium is 7.09% of income, but there's a backdoor that's wide open. For average wage earners, after excluding the company's 50% contribution, it amounts to about 100,000 to 300,000 won per month. However, it's different for the rich. The monthly maximum insurance premium cap is 8.48 million won, meaning 7.09% is deducted until reaching this amount. This applies to people earning 120 million won per month. They pay nearly 100 million won annually in health insurance premiums. 박재일. (2024, March 18). [박재일 칼럼] 부자들이 내는 의료보험. 영남일보. https://www.yeongnam.com/web/view.php?key=20240317010002206

UK: 20%

Most employees pay 8% on earnings between £12,584-£50,284. Employers add 13.8% above £9,100. With UK median salary at £34,963, total National Insurance hits 20% of income (source).

Japan: 9.98%

Tokyo's health insurance rate is 9.98% (March 2024), split equally between employee and employer. Rates vary by region and update every six months (source).

Norway: 21.9%

Employees pay 7.8%, employers pay 14.1% (source, source).

The scheme is financed by the individual's and employer's social security contributions in addition to grants from the state and the municipalities. The individual's contribution is charged at a higher rate for self-employed persons (11%) than for employees (7.8%). The employer's contribution (14.1%) must be paid with respect to salaries, etc. The rates are determined by the Parliament in the annual decrees on contributions to the National Insurance Scheme. https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/norway/individual/other-taxes

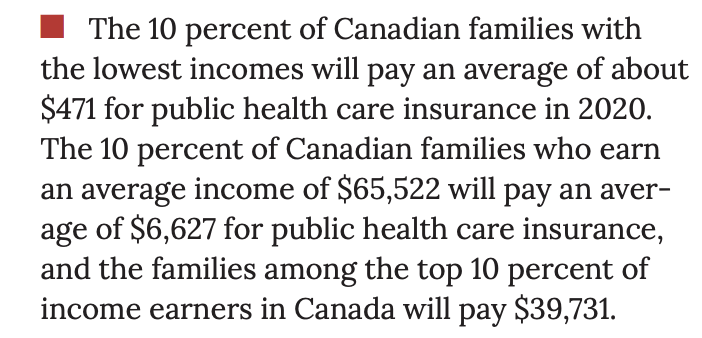

Canada: 10%

Canada has no direct healthcare tax-the federal government transfers funds to provinces. The Fraser Institute's 2020 report estimates the implicit cost (source):

No perceived alternative career paths

This year's CSAT had the highest proportion of repeat test-takers in 28 years-only 65% were current students. Everyone wants medical school.

Students abandon their interests for medicine's guaranteed income and security. Of 1,121 public university admissions, 911 (81.3%) were repeat test-takers.

Korea has 6-year undergraduate medical programs, then internship, residency, fellowship like the US. The shocking part is the rigid ranking of university-major combinations:

The image shows university-major rankings. "의예과" (medicine) and "치의예과" (dentistry) dominate. A random state school's medical program outranks Seoul National University's computer science. Korea's brightest minds default to medicine.

Why? Korea lacks the three economic engines that create leverage beyond natural resources:

- No finance: MITI-style development killed foreign investment (see "Korea discount" source)

- No entrepreneurship: No liquidity (source) + "startup = fried chicken restaurant" mentality

- No research: Underfunded graduate programs and labs

- No resources: No oil, metals, coal, decent lumber, or clay

Potential solutions

Four realities to understand first:

- Specialties differ by insurance coverage levels

- Hospital tiers serve different populations

- Higher fees mean nothing without bigger budgets

- Punishing dermatology won't create emergency doctors

The solutions are obvious:

Increase consultation fees to allow doctors to spend more time with patients

Doctors see 120 patients in 3 hours-1.5 minutes each. Higher consultation fees would enable real patient care. This would also curb "과다 의료" (excessive visits) for minor issues. Pair fee increases with policies discouraging unnecessary visits.

Increase fees by 2-5x for difficult operations performed by avoided specialties

Emergency medicine, obstetrics, and surgery fees are insulting. Multiply them by 2-5x. Target high-skill, high-risk procedures. Make essential specialties financially viable.

Restore honor and provide support for doctors in avoided specialties

Fix the hostile environment:

a) Legal reform: Match international standards. Korea's 0.5% annual prosecution rate (vs. Japan's 0.01%) terrifies doctors in high-risk fields.

b) Recognition: Extra compensation, bonuses, better working conditions. Make essential specialties respected again.

Implement a strong primary care system with family doctors or general practitioners as gatekeepers

Rebuild primary care:

a) Mandatory referrals: See primary care first, get referred up (emergencies excepted)

b) Better pay and status: Make primary care attractive

c) Public education: Teach appropriate healthcare usage

Implement guardrails to direct tertiary care access and incentives for primary care

Stop tertiary hospital abuse:

a) Strict referrals: No tertiary access without referral (true emergencies excepted)

b) Financial penalties: Higher co-pays for direct tertiary visits

c) Focus tertiary hospitals: Cut reimbursement for simple procedures at big hospitals

d) Upgrade regional hospitals: Reduce Seoul medical tourism

Predictions

None of these solutions will happen. Here's the likely trajectory:

- Doctors continue 30 years of futile protests

- Public remains ignorant of root causes

- Politicians avoid hard choices

- Hospitals collapse financially

- Insurance privatizes

- US-style healthcare inequality emerges

- Public demands better care

- Government nationalizes hospitals-doctors become civil servants

- Top talent flees Korea

- Care quality plummets

- Rich Koreans seek treatment abroad

This healthcare collapse is one symptom of Korea's broader decline since Moon Jae-in's presidency. The real estate bubble will destroy the middle class. Legislative barriers and militant unions strangle innovation. Only Samsung and content exports (BTS, webtoons, gaming) keep Korea afloat. Without them, Korea becomes China's satellite. That's another post.