Economic wealth is a three-body problem.

Energy sets the ceiling: how much raw power a society can summon. Hardware sets the plumbing: the machines that turn power into work. Software sets the choreography: the knowledge that tells the machines what to do.

You can see the triad in miniature. A person runs on food, moves through muscles, and acts on learned skill. A tree draws sunlight, channels it through trunk and leaf, and follows instructions written in DNA. History is the same story at civilizational scale—long stretches where one term is the bottleneck, interrupted by rare moments when two, or all three, move at once.

With that lens, the past stops looking like a parade of inventions and starts looking like constraint relief.

The Agricultural Baseline (10,000 BCE – 1400 CE)

For most of recorded history, all three factors were locked. Energy came from food: human muscle, draft animals, burning wood. Hardware meant simple tools—plows, hoes, irrigation ditches—built from whatever nature offered and requiring constant biological input to operate. Software was oral tradition: crop rotation, seasonal calendars, folklore about when to plant. Each generation relearned most of what the previous one knew; without writing, knowledge leaked as fast as it accumulated.

There were exceptions—clever hardware that borrowed from gravity and moving water. The waterwheel, appearing in antiquity, let rivers grind grain instead of slaves. The Archimedean screw lifted water for irrigation without buckets. Aqueducts moved water across miles using nothing but carefully calculated slope. Levers, pulleys, and counterweights let builders raise stones no team of men could lift directly. By the medieval period, windmills dotted the European landscape, and cam mechanisms converted rotary motion into the repetitive pounding needed for fulling cloth or forging iron. These were real gains—but they were localized, dependent on geography, and couldn't scale beyond what wind and current provided. They softened the constraint without breaking it.

The result was a civilization in equilibrium. One farmer could feed two or three people. Ninety percent of the population worked the land. Progress, when it came, took centuries to spread.

The Software Breakthrough (1400 – 1700)

The Renaissance changed what humans knew long before it changed what they had. Energy stayed biological; windmills and watermills helped at the margins but didn't break the constraint. Hardware advanced in targeted ways—the printing press for copying ideas, precision clocks for coordination, lenses for seeing the very large and very small.

The real unlock was methodological. The scientific method gave humanity a recipe for generating reliable knowledge: observe, hypothesize, test, record. Mathematics leapt forward with calculus and probability. Physics offered predictive laws. And crucially, the printing press meant each generation could build on discoveries rather than rediscover them.

Knowledge, for the first time, compounded. That compounding taught an uncomfortable lesson: the new bottleneck wasn't thinking—it was power.

The Energy and Hardware Revolution (1760 – 1840)

Once ideas could accumulate, they pointed directly at the constraint: biological energy was too weak. Coal answered the call—24 MJ per kilogram versus wood's 16—and the steam engine learned to convert that heat into motion without muscles.

The implications cascaded. Steam engines ran continuously, day and night, indifferent to fatigue. Factories concentrated machines under one roof. Railways shrank distances. Iron production scaled. For the first time in human history, available energy exceeded what biology could provide by a factor of ten to a hundred.

Software trailed behind, mostly organizational: standardized parts, patents, early industrial engineering. But the leverage came from unlocking two factors at once. One farmer could now feed ten or twenty people. Cities swelled as agricultural labor needs collapsed.

Distributing Power (1870 – 1914)

The first industrial revolution made energy; the second learned to move it. Electricity traveled through wires to wherever it was needed. Petroleum, denser still at 46 MJ/kg, powered internal combustion engines light enough for personal vehicles. Power grids turned centralized generation into distributed consumption.

Hardware followed: assembly lines, automobiles, telegraphs and telephones, electric motors precise enough to place exactly where the work was. Software caught up with the organizational demands—Taylorist management, corporate hierarchies, chemical engineering (Haber-Bosch alone enabled the population boom of the twentieth century).

Productivity per worker increased tenfold. Consumer goods became cheap enough for ordinary people. The wealth wasn't just created; it spread.

"Software" Eats the Surplus (1950 – 2000)

By mid-century, energy and hardware were abundant enough that the binding constraint flipped back to software—but in a new way. The transistor arrived, then integrated circuits, then chips dense enough that no human could design them unaided. Hardware had grown too complex for intuition; you needed software (accumulated knowledge of math and physics) just to build the next generation of hardware. Moore's Law wasn't a law of physics—it was a law of compounding knowledge encoded in design tools.

The same pattern played out across industries. You couldn't engineer a modern jet engine, optimize a supply chain, or sequence a genome without software mediating between human intention and physical reality. Programming languages, databases, and algorithms became the substrate on which hardware design itself ran.

Knowledge work overtook physical labor as the dominant source of wealth. The companies that wrote code grew more valuable than the companies that pumped oil—not because code was the product, but because code had become the bottleneck for making everything else.

Software Everywhere (2000 – 2020)

The next phase wasn't a new factor—it was software's conquest of the remaining territory. Smartphones put a supercomputer in every pocket. Cloud data centers made compute elastic. Sensors proliferated: cameras, GPS, accelerometers. Broadband made all of it instantly accessible.

Machine learning introduced software that improved with data rather than explicit instruction. Platforms—iOS, Android, AWS, social networks—became the substrate for entire economies. SaaS replaced ownership with subscription. "Software is eating the world" stopped being a slogan and became a description.

Energy kept pace through renewables and lithium-ion batteries. Hardware shrank and multiplied. But the value capture tilted overwhelmingly toward code.

The Convergence (2020 – Future)

We are entering the first era where all three factors may advance simultaneously and dramatically.

- Energy: Fusion promises nearly unlimited clean power; advanced batteries and smart grids will store and route it.

- Hardware: Humanoid robots approach general-purpose physical labor; quantum computers tackle problems classical machines cannot; brain-computer interfaces merge cognition with silicon.

- Software: Large language models handle natural language with startling fluency; computer vision reaches superhuman accuracy in narrow domains; autonomous systems move from demos to deployment.

If even half of these trajectories hold, the economics invert. Labor costs collapse. One person augmented by AI could match the productive output of a small company.

Compounding and the Shape of Progress

History suggests a pattern. When one factor moves alone, growth is linear—agriculture advanced slowly for millennia. When two factors move together, growth turns exponential—the Industrial Revolution created more wealth in a century than the previous ten thousand years combined. When all three move at once, the curve steepens again.

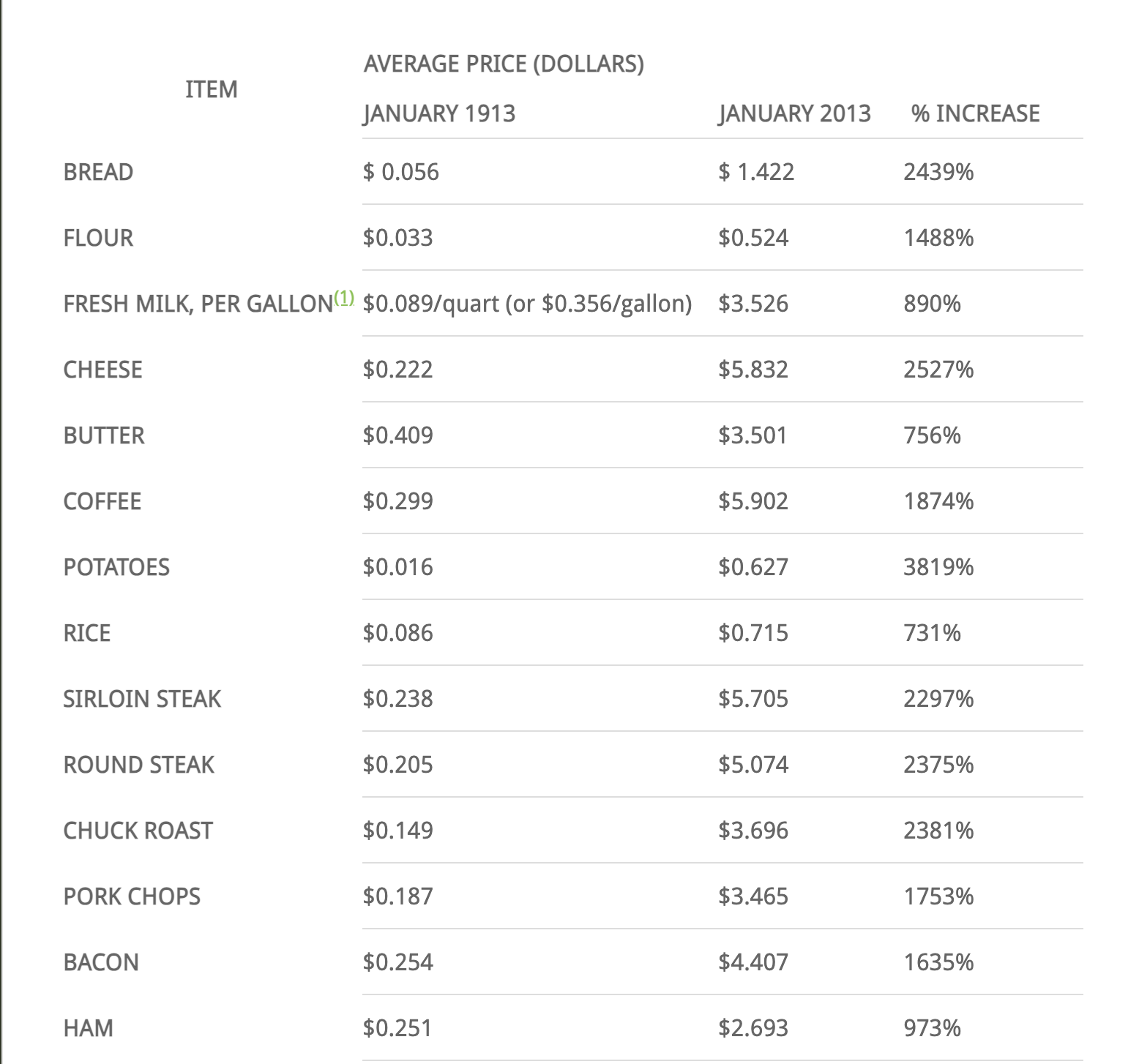

InflationData.com (2013). "Food Price Inflation Since 1913".

Despite monetary inflation—$1 in 1913 equals roughly $32 today—real prices have plummeted across nearly every category. U.S. cheese production grew from 418 million pounds in 1920 to 14 billion in 2023; population tripled, output multiplied by 33. Each era's breakthroughs didn't just add to previous gains; they multiplied them. Renaissance software × Industrial energy yielded 10× productivity. Industrial hardware × Information-Age software yielded 100×. The coming convergence hints at 1,000× or more.

Why This Matters Now

A tree doesn't decide to grow; it expresses a program under constraints. Civilizations do something uncomfortably similar—except we can, sometimes, choose which constraints to relieve.

We are living through the final years before this convergence reshapes everything. The question is no longer whether abundance is coming. The question is who will control the means of creating it—and whether we can evolve the system fast enough to distribute the gains before the disruption destabilizes it.

Political debates about redistribution assume a fixed pie. We should not fight over today's pie. We should be building an infinite bakery. The real problem is making sure the bakery doesn't explode on the way there.

Zero-sum thinking—the reflex of old oligarchs and anxious electorates alike will not help. Technology has always been humanity's primary tool for reducing suffering and expanding possibility. As energy, hardware, and software converge, they will redefine what abundance means. The only question left is whether we're ready to update our institutions, and our imaginations, to match.